“You know what it means to be close to a power plant? Being close to trouble.” Tiger B., is 41 years old, though he seems sixty. He has always worked as a welder in the coal-fired power plant, Duvha Power Station, near Emalahleni. It’s an appropriate name for a mining city: in the Nguni language “Emalahleni” means “place of coal.”

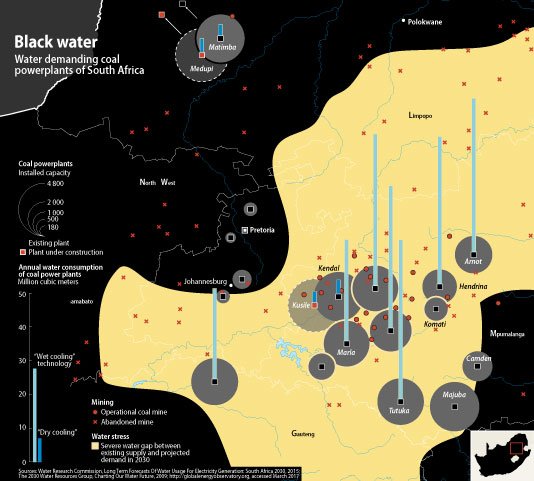

His life and that of his family’s are in harmony with the rhythm of the 3,600 Megawatt power plant. The owner of the plant is Eskom, the state-owned electricity utility company and for years now the largest in South Africa. The coal mine feeds energy production, and black smog covers both the village and also Tiger’s lungs, which are clogged with phlegm and dust. “Do you see the high-voltage cables and water pipes? They are for the power plant. But in the village we have neither electricity nor water. Hundreds of thousands of liters per minute are used to cool the turbines that generate energy sold to Swaziland and Mozambique. For us, we live in the dark and get three and a half liters of water per day that we carry in a tank.” In the makeshift village, almost 5,000 people live stacked beside a coal wall and a black water well, waiting every week for the small community cistern to be filled. “People often argue furiously for a few more liters,” says Lucky, who prefers not to use his full name for fear of retaliation, passing a dirty cigarette to Tiger. “Coal is stealing our right to water and air.”